The Care-Centered Economy: A New Theory of Value

David Bollier

I recently encountered a brilliant new essay by German writer Ina Praetorius that revisits the feminist theme of “care work,” re-casting it onto a much larger philosophical canvas. “The Care-Centered Economy: Rediscovering what has been taken for granted” suggests how the idea of “care” could be used to imagine new structural terms for the entire economy.

By identifying “care” as an essential category of value-creation, Praetorius opens up a fresh, wider frame for how we should talk about a new economic order. We can begin to see how care work is linked to other non-market realms that create value — such as commons, gifts of nature and colonized peoples –all of which are vulnerable to market enclosure.

The basic problem today is that capitalist markets and economics routinely ignore the “care economy” — the world of household life and social conviviality may be essential for a stable, sane, rewarding life. Economics regards these things as essentially free, self-replenishing resources that exist outside of the market realm. It sees them as “pre-economic” or “non-economic” resources, which therefore don’t have any standing at all. They can be ignored or exploited at will.

In this sense, the victimization of women in doing care work is remarkably akin to the victimization suffered by commoners, colonized persons and nature. They all generate important non-market value that capitalists depend on – yet market economics refuses to recognize this value. It is no surprise that market enclosures of care work and commons proliferate.

A 1980 report by the UN stated the situation with savage clarity: “Women represent 50 percent of the world adult population and one third of the official labor force, they perform nearly two thirds of all working hours, receive only one tenth of the world income and own less than 1 percent of world property.”

But here’s the odd thing: The stated purpose of economics is the satisfaction of human needs. And yet standard economics don’t have the honesty to acknowledge that it doesn’t really care about the satisfaction of human needs; it’s focused on consumer demand and the “higher” sphere of monetized transactions and capital accumulation. No wonder gender inequalities remain intractable, and proposals for serious change go nowhere.

“The Care-Centered Economy” asks us to re-imagine “the economy” as an enterprise focused on care. While Praetorius’ primary focus is on the “care work” that women so often do – raising children, managing households, taking care of the elderly – she is clearly inviting us to consider “care” in its broadest, most generic sense. The implications for the commons and systemic change are exciting to consider.

I think immediately of the Indian geographer Neera Singh, who has written about the importance of “affective labor” in managing forest commons. Singh notes that people’s sense of self and subjectivity are intertwined with their biophysical environment, such that they take pride and pleasure in becoming stewards of resources that matter to them and their community.

Such affective labor – care – that occurs within a commons becomes a force in developing new types of subjective identities. It changes how we perceive ourselves, our relationships to others, and our connection to the environment. In Singh’s words: “Affective labor transforms local subjectivities.” In this sense, commoning is an important form of care work.

By setting forth an expansive philosophical framework, Praetorius’ essay provokes many transdisciplinary, open-ended questions about how we might reframe our thinking about “the economy.” The 77-page essay, downloadable here, was recently published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Berlin as part of its “Economy + Social Issues” series of monographs.

Praetorius begins by situating the origins of “women’s work – children, cooking and church – in the original “dichotomization of humanity” into “man” and “nature.” This artificial division of the world into realms of man and nature lies at the heart of the problem. Once this “dichotmomous order” is established, the public realm of monetized market transactions is elevated as the “real economy” and given gendered meaning. Men acquire the moral justification to subordinate and exploit all those resources of the pre-economic world – nature, care work, commons, colonized people. Their intrinsic needs and dignity can be denied.

What’s fascinating in today’s world is how the many elements of the “pre-economic lifeworld” are now starting to assert their undeniable importance. As Praetorius puts it, “Without fertile soil, breathable air, food and potable water, human beings cannot survive; without active care, humanity does not reproduce itself; and without meaning, people descend into depression, aggression and suicide.”

As the pre-economic lifeworld becomes more visible, it is exposing the dichotomous order as unsustainable or absurd. Climate change is insisting upon limits to economic growth. Modern work life is becoming ridiculously frenetic. Questions of meaning arise that “free markets” are unequipped to address. “Why work at all if working amounts to nothing more than functioning for absurd, other-directed purposes?” writes Praetorius. “Why keep living or even conceiving and bearing children if there is no future in sight worth living?”

As the private search for meaning intensifies, the formal political system has little to say. It is too indentured to amoral markets to speak credibly to real human needs; it is ultimately answerable to the highest bidders. This also helps explain why politics, as the helpmate of the market order, also has so little to say about people’s yearnings for meaning.

But new meaning are nonetheless arising as the credibility and efficacy of the old order begin to fall apart. Praetorius argues that the anomaly of a black man as US President and a woman as Germany’s chancellor makes it increasingly possible for people to entertain ideas of subversive new types of order. “The supposedly natural order of the hierarchical, complementary binary conception of gender is inexorably disintegrating,” writes Praetorius. Other dualisms are blurring or becoming problematic as well: “belief and knowledge, subject and object, res cogitans and res extensa, colonizer and colony, center and periphery, God and the world, culture and nature, public and private spheres.”

What’s exciting about this time, she suggests, is that the “dichotomous order” is opening up new spaces for new narratives that re-integrate the world. People can begin to “collectively dis-identify” with and deconstruct the prevailing order, and launch new stories that speak to elemental human and ecosystem needs. If there is confusion and disorientation in going through this transition, well, that’s what a paradigm shift is all about. In any case, people are beginning to recognize the distinct limits of working within archaic political frameworks – and the great potential of a “care-centered economy.”

What exactly does “care” mean? It means the capacity for human agency, individual initiative yoked to collective practice, shared identity and meaning-making. It means “being mindful, looking after, attending to needs, and being considerate.” It refers to “awareness of dependency, possession of needs, and relatedness as basic elements of human constitution.”

While some might regard the elevation as “care” as vague, I agree with Praetorius: “Care” helps break down the dichotomous order and emphasize the “pre-economic” order of human need. “The illusion of an independent human existence becomes obsolete,” she writes. Relationships outside of markets become more important.

Introducing “care” into discussions about “the economy” can also have the effect of transforming ourselves. We can begin to name the pre- and non-economic activities — care, commoning, eco-stewardship – that create value. We can develop a vocabulary to identify those things that mainstream economics deliberately does not name. In this sense, talking in a new way becomes a political act. It begins to change the cultural reality, one conversation at a time.

Praetorius’ essay is a fairly long read, but a rewarding one. I came away from it with a fresh, more hopeful perspective. I also realized how care work and commoning are part of a larger enterprise of honoring, and creating, new types of value.

Originally publshed at bollier.org

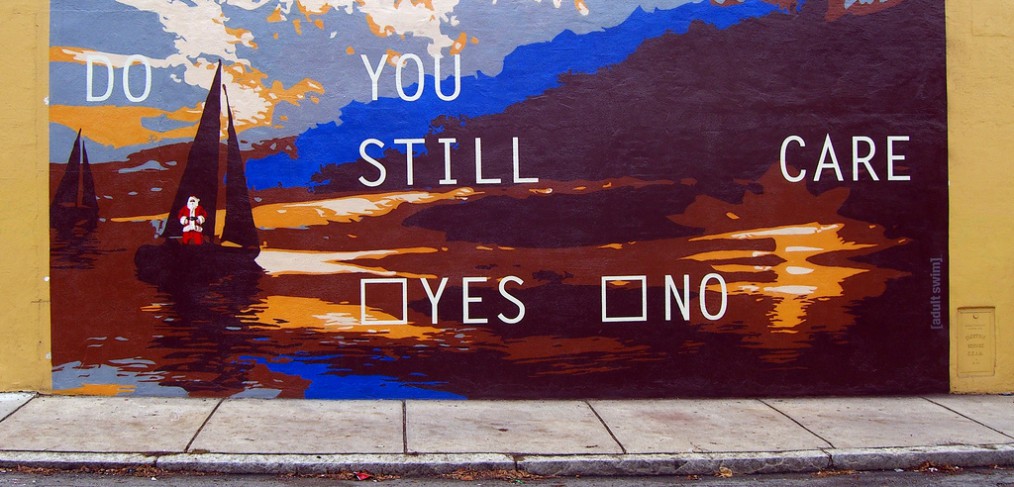

Lead image by WalknBoston