Imagining the (R)Urban Commons in 2040

Silke Helfrich

I was delighted to give a key-note talk at the First IASC Thematic Urban Commons Conference last week in Bologna. Here are my speech and the slides. The most beautiful ones were produced by Nikolas Kichler.

In 2040, one generation from now, I will be more than 70 years old and hopefully surrounded by my first great-grandchildren. What I’d like to share with you this morning is how I imagine* the Urban Commons will be by then – and how I’d like my grand- and great-grandchildren and me to enjoy them and care for. Actually, first of all: While rethinking the issue of this conference, I realized that it should read: Imagining the “Rurban Commons.” Because this seems to be one of the most important patterns: Interconnecting Urban and Rural. The so called Urban Agriculture or rural Maker-Spaces like the OTELOs throughout Austria are pioneering this inter-connection.

- THE SLIDES: Imagining the (R)Urban Commons in 2040

- (The effects of the presentation have unfortunately gone with the conversion to pdf.)

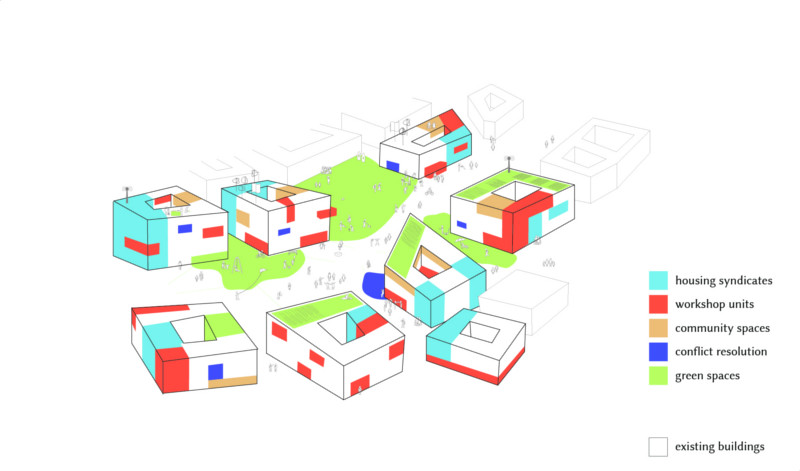

So, to share how I imagine the future of the rurban commons, I’d like to invite you to take a collective walk with me – a walk through an environment that we can co-create, that in fact can only be co-created. Step by step and adapted to the local circumstances. Designing such an environment doesn’t automatically ensure or guarantee “urban commons”, but it can provide the conditions and infrastructures for commoning.

This is crucial for the insight that Peter Linebaugh phrased as follows: There is no Commons without Commoning. I believe, that the most challenging and indispensable factors, which make commons come true, are to (learn how to) think like a commoner and practice “how to common” at the same time. And this, in turn, requires a specific attitude. An attitude based on the recognition of a simple truth: We are all related to each-other!

“I am because you are”, or “I am through the others.” Also known as ubuntu. Just have a closer look at the word “I“. This is a relational term. Saying “I” doesn’t make sense if there is no “You”. This is at the very core of the paradigm shift that the commons-debate contributes to. To put it differently: Human beings are free in relatedness but never free from relationships. That’s the ontological bottom line. Relation precedes the things being related to, i.e. the actual facts, objects, situations and circumstances. Just as physics and biology are coming to see that the critical factors in their fields are relationships, not things, so it is with commons.

From this insight, we can then see that, commoning can be conceived as a way of living. It is a life-form that (potentially) enacts freedom in relatedness, which is a sometimes hurtful, mostly bumpy and always complex social process. And a process that requires us to constantly swim upstream, against all odds, because in a capitalist society we tend to systematically disregard the capacities and skills we need for it.

Anyway: Commoning means: take collective action to enact the Commons. The more consciously and self-consciously this happens, the better.

To what extent is this relevant for this conference?

One of the aspects that distinguishes the modern commons-debate from the debates 150, 40 or only 20 years ago is, that there is more and more interest in exploring and understanding how free cooperation (commoning) works among strangers, and how it can be made stable and durable. People also want to understand how commoning might work in nontraditional communities; in networks, in the digital world, in multiethnical contexts, among “nomadic citizens” such as hackers and migrants, and so on. The bet is: this is perfectly possible…

- if the Patterns of Commoning are as well understood as the (Ostrom) Design Principles for Commons Institutions;

- if they are appropriated and cultivated and become an embodied experience;

- and if we dispose of (free) communication tools to enable our cooperation.

Commoning is beyond the just “being together” (more than Geselligkeit, as we would say in German). In fact, it may be the only way in which we can systemically confront the dysfunctions and corruptions of the market/state system that now govern us.

Now, let’s beam into the year 2040 and start our walk.

Picture the city you live in or a city you know well. Focus on a certain neighbourhood and remember the bustle in the streets. Remember how this place sounds and smells like and what people are doing there…. A city is fluid, which means that such a neighbourhood is changing constantly. People move in and out. Buildings are bought and sold, shops close down and others open up. Infrastructures change sometimes more quickly than we wish them to do. Once there was a factory. Now there is a cultural centre. People disconnect from traditional work-places; they work at their home office or in the co-working space next door. Each change of the kind is also an opportunity to “commonify” the city.

You may find this an odd statement. So let me show you what this might look like. First and foremost: The main focus is on rethinking use. In fact, a commons approach can make new constructions unnecessary. There are surprising solutions to underuse. Everywhere. “Zwischennutzung” (in-between-use?) is only one of them.

Or apartments can be converted into co-housing projects (yes, this is different from Airbnb). Co-housing means; sharing basic housing infrastructures according to peoples needs, in a self-determined and durable way, not renting a flat every now and then. This has two major effects: it helps people to become more independent from the housing market. And this in turn helps to “free” the houses or apartments from concentrated market control, speculation and artificially high prices.

Of course, there is an endless number of legal forms from housing cooperatives to community land trusts. But the crucial point here is to make sure that once something is in the commons, it shall remain in the commons and not fall back into the market. In Germany, there is a robust and growing institution called “Mietshäusersyndikat” (sth. like the Federation of Housing Commons). It has more than 25 years of experience in co-facilitating the self-organization of hundreds of housing units all over the country. They co-created a solidarity and co-financing network among housing projects. But what makes them really special is the legal tweak, the smart legal arrangement they’ve developed to protect the buildings/houses themselves as a commons. It has been done in such a way that it is very difficult to resell a co-housing project back into the market. What the federation of housing commons is basically doing is: to elevate the freedoms of commoners at the expense of investors, speculators and often, governments. They protect the freedoms that money can’t buy.

To me: Mietshäusersyndikat is kind of the Copyleft for Housing projects.

Why is this important? Because doing this means widening the sphere of the commons with a long term perspective. And widening the sphere of the commons entails shrinking the sphere of the market and vice versa. So, remember: Each Commons needs protection!

Let’s walk on

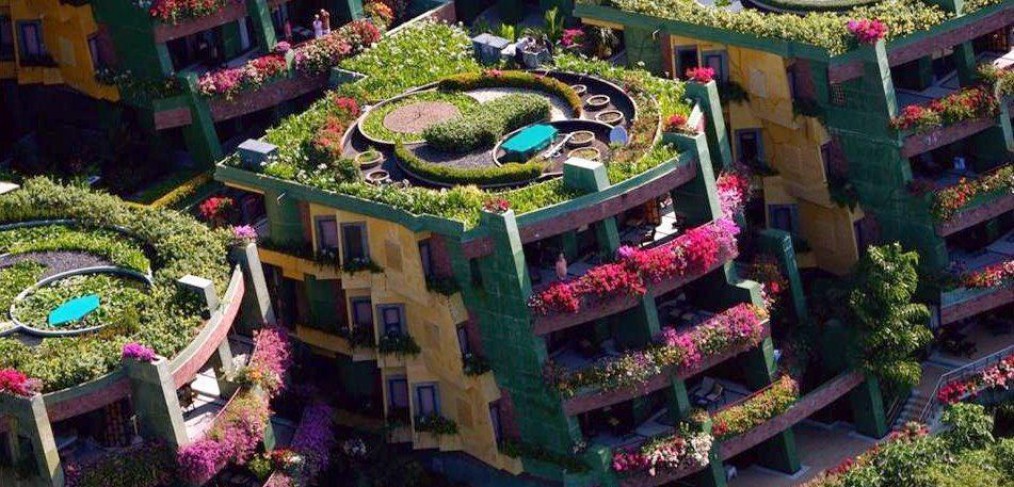

Everybody needs not only shelter but also something to eat. And a decisive part of the reintegration of rural and urban functions is certainly more food production in the city. In my great-children’s Rurban Commons, there will be spaces for experimental gardening and herb commons – you might already know the concept of an edible city. All this would be part of.

There would be a bee and wild bird yard, the already famous community gardens and intercultural gardens. There would be flower fields, fruit tree zones … you name it. And, of course, CSAs. CSA means Community Supported Agriculture. This is crucial, because – as in the co-housing case – the functioning of many CSAs successfully disconnects food-production from the imperatives of the market and instead initiates a kind of “pool & share” approach.

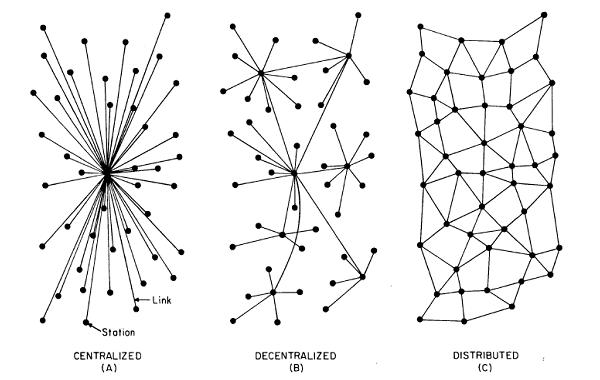

As you might have noticed, for me, the commons is much more than a concept of togetherness: it also describes a new mode of production. Of potentially everything: housing and food, software and hardware, furniture and machines, health and educational services; if possible in a distributed (not decentralized) way. Decentralization is better than centralization, but still a top – down approach. A distributed scheme of production is different. This is what we can learn from the P2P communities.

One could say: We are witnessing a worldwide field try, and an expansion of locally proven models of this new way of production. Open hardware projects are mushrooming, as CSAs do. They often use different concepts and wordings. This is part of why the common DNA of all these experiments, the patterns of commoning, often remain unvisible.

Let’s have a closer look.

In the place I will live in 2040, there will be a repair-café, a laundry saloon, outdoor workshops for whatever purpose, a tool lending library, fab labs a building physics workshop, a hackerspace, a fabric sharing & tailoring space, and so on.

The infrastructure will be controleable and controlled by the neighbourhood: there is (distributed) renewable energy production, a sewage purification plant, Open Wifi and Open Network. There are fire brigades, health & first aid associations and much more. There is a common pattern (I refer to patterns as used in the Patterns Theory and Pattern Language approach by Christopher Alexander) in the kind of infrastructure I think of: platforms are/platform use is free of discrimination.

Such platforms are based on the principle that more money doesn’t entail more use rights (compare it to the concept of net-neutrality; you could call it platform-neutrality).

Let’s continue strolling around the neighbourhood:

There are the cultural spaces for the unfolding of cultural activities, reading circles, an open theatre, a contemplation area, a library, an open permaculture and a commoning school and so on. Many of them are simply open spaces for non determined uses. And finally, we need to get around within and beyond the neighbourhood. I imagine mobility in a rurban commons as a combination of bikes, p2p car-sharing and good connectivity to public transportation.

So, is this realistic? Or is it utopia, that is: a “non-place”?

I think it is something that the German philosopher Ernst Bloch calls: “Concrete Utopia”. We can already grasp such a transformation. The experiences are there, still scattered, and named in great many different ways. But they are there. The needs are there as well. And the commons is a needs-based approach (more than a rights based approach). From where what is now “individual property” [and a tragedy of the anticommons – the fragmentation of property rights, and thus a social and economic paralysis] can be transformed into shared possession, according to people’s needs and decisions.

That’s what the commons framework is all about: in essence it’s a way to meet people’s needs at all levels. It’s a way of provisioning that doesn’t need to be achieved through:

- individual property as default position

- nor mediated through the so called “market mechanisms”. (In fact, mechanistic metaphors are very misplaced when we try to understand and address the complexity of social relationships)

So, how do we get there?

Let’s go back to the year 2015 and have a look at where it all began: part of this emerging Rurban Commons era was the First IASC Thematic Conference on the Urban Commons.

And let’s have a look at what’s out there.

OMNI-COMMONS

You see, the experiments are there, the concepts are there. And even mapping tools to make visible what’s still invisible.

We need more than an Omni-Commons everywhere. We need to discover the common patterns of the initiatives that experiment with a rurban commons approach and we need to help to connect them – not necessarily in physical terms, but mentally and politically. Because one thing is for sure: we are not just for dealing with “the left overs”, or in urban terms with “vacant terrain” – or what used to be called “wastelands.” It is not about the peripheral undefined edges of the city. It’s about rethinking the rurban environment as commoners. Social and cultural realities are not facts, they are something we co-create.

So: connect commons → confederate the hot spots of commoning → create commons-neighbourhoods → commonify the city. In short: Widening the space for the commons while shrinking the space of the market is feasible. It needs to be enabled, done and (politically and academically) supported. Of course, such an approach needs a consistent framework, so that people feel mirrored in it, so to speak.

This is where commoners on the ground need the help of scholars, of engaged scholars as you are. Scholars who don’t just study what they do and what they don’t do, but co-facilitate the co-creation of a free, fair and sustainable society. As Ezio Manzini put it last night:

“Commons are fluid forms. To enact them we should focus on enabling conditions, not on fixed designs.”

That was precisely what I was trying to do: take you on a walk through a non-fixed design that is meant to create the enabling conditions for commons in a rurban environment. A “design” that is open and allows for constant adaptation. It was called: CITY OF WORKSHOPS. And it was not me who did it. But two young participants of this conference who care for commons and the creation of enlivened rurban environments: Nikolas Kichler and David Steinwender from Austria.

So, there is hope, not only for one generation from now but within the next generation.

There is power in the Rurban Commons if there is Power in the Communities, that make, care for and protect them. Therefore: Keep calm and Keep Commoning.

*words in bold are illustrated on the slides.

Update Nov. 13: Blogpost with more information on the Conference: The City as a Commons by David Bollier

Images by Nikolas Kichler and Brian (Ziggy) Liloia: Main image “Botanical apartments in Phuket Thailand”, author unknown.